Book review: The Honest Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone - Especially Ourselves

I first learned about Dan Ariely through his book, Predictably Irrational.

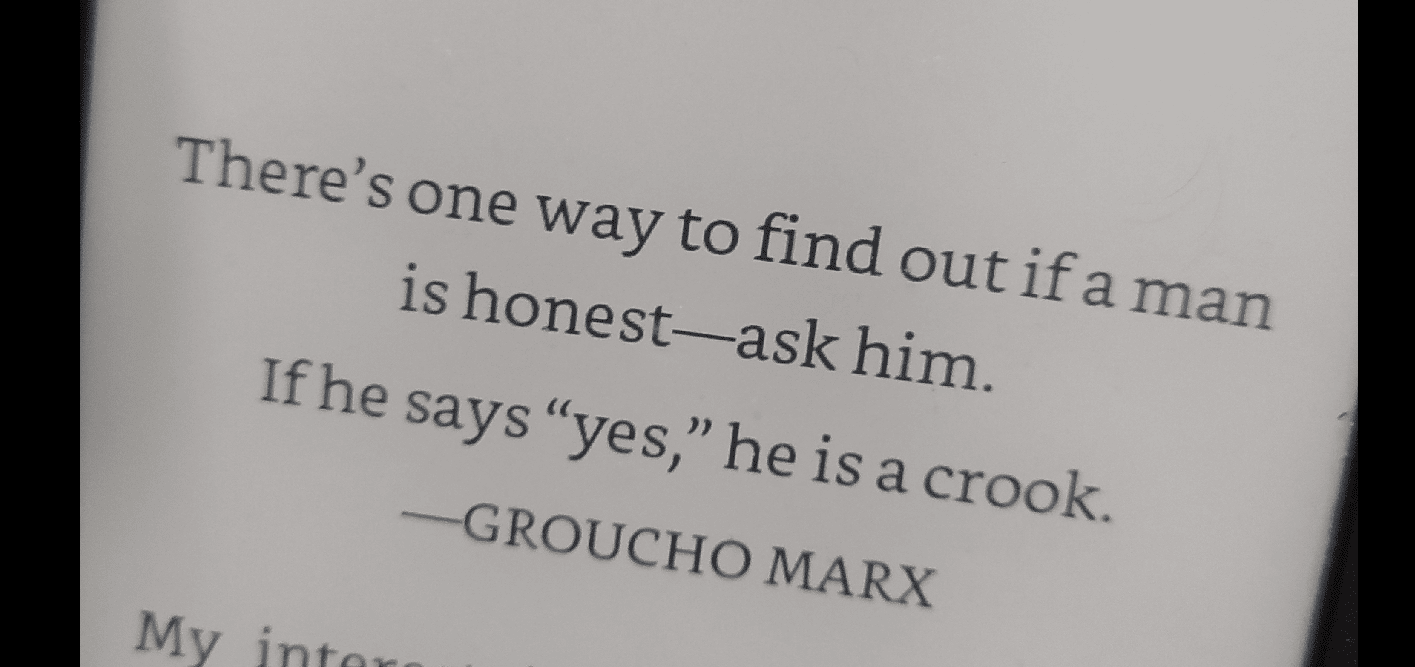

It appears we all are dishonest with minimally varying fudge factors. In fact, someone who insists they are completely honest might be the most suspect. Let's explore this dishonesty within us.

Experiments show that cheating and dishonesty aren't primarily driven by the potential gain (money or value) or strict rules like having supervisors. Instead, we each have an internal limit – a fudge factor – that allows us to cheat just enough to benefit without feeling like a bad person.

Interestingly, when the reward for cheating is not physical money but something else, people tend to be more dishonest or at least tend to rationalize cheating more easily. This can possibly suggest a cashless society could potentially lead to more cheating.

To reduce the fudge factor, experiments indicate that moral reminders can help lower dishonesty in the short term, although their effect may not last long.

In a golf experiments where no referee is present and cheating is simple, a pattern of dishonesty emerged among golfers. The results indicated that when there was a greater psychological distance from the act of cheating itself, people cheated more readily. This highlights our human inclination to be dishonest when we can find ways to rationalize dishonesty.

Conflicts of Interest and Dishonesty

Conflicts of interest are another factor that has been experimentally demonstrated across various professions, from medicine to finance. These situations reveal how personal interests can compromise honesty. While complete elimination is nearly impossible, potential solutions include implementing regulations or actively working to reduce such conflicts.

Dishonesty When Tired (Ego Depletion)

We are more likely to act dishonestly when we are tired or depleted. This state, sometimes referred to as "ego depletion," occurs when our mental resources are exhausted. In everyday life, whether managing work, adhering to a diet, or following an exercise routine, we are more prone to give in to temptations and abandon our commitments when we reach our limits. The recommended approaches to mitigate this include either strategically choosing to disengage from certain challenges to conserve energy for others, or proactively avoiding tempting situations rather than confronting them head-on.

Wearing counterfeit and dishonesty

Studies show that wearing fake products might actually make people act more dishonestly. In experiments, those wearing counterfeits were more likely to cheat. Interestingly, these same people also tended to believe others were more dishonest. So, wearing fakes seemed to increase both their own dishonest behavior and their suspicion of others.

Ariely found that once an individual gives in to temptation (what the hell), it is much easier to cave in the next time temptation surfaces. This connects to the "what the hell" effect. It's like when you're on a diet and cheat once; you might think, "what the hell," and keep cheating or give up entirely. Similarly, the first time someone acts dishonestly, even in a small way, it can open the door for more dishonest actions later on. That's why those first dishonest steps are really significant, as they can start a chain of dishonest behavior and moral deterioration.

Dishonesty and self deceptionSelf-deception appears to be a prevalent aspect of human behavior. As demonstrated by the work of behavioral economist Dan Ariely and his colleagues, engaging in dishonest acts, even seemingly minor ones like cheating on a test, can lead individuals to inflate their self-assessment of their abilities.

In a series of experiments, participants were given tests and presented with opportunities to cheat by viewing the answers. The findings revealed that those who cheated subsequently reported higher estimations of their performance and capabilities, despite their awareness of their dishonest behavior. This suggests a compelling link between the act of cheating and the ability to deceive oneself, leading to a distorted, often overly positive, self-perception.